Homeschooling a Special Needs Child

I am a huge advocate for families homeschooling their children with special needs. I believe schools are high stress, low engagement, and very punishing environments for children who learn out of the box. Parents are vested in the overall well-being of their children and know their children the best. This makes parents who can manage it, the best educators for these children.

It is easy to become overwhelmed, though, when your job extends from parenting to include educating. In the years I have worked in education, I have applied the following methods in both home and classroom, with children who meet milestones at targeted times, and with kids who exceed or do not meet milestones. The methods themselves are the outline. The implementation is consistent. The resources may change and the goals may change, though. This is why these methods fall under the term “eclectic” academics, and they are as individualized as your child is. With information, support, and strategies families can help their children receive an “appropriate education” with higher quality and less stress then going through the school system.

This Starts with a Realistic Assessment

The first thing to do is to realistically assess where your child is academically. This can be hard. For example, your child may make syllabic sounds throughout the day, but will not imitate them for another person, or use them functionally. An older child may have answers that sound correct, but are actually memorized scripts that they apply to a similarly worded question without understanding the nuance or function of the words. If an action was observed once, that’s a great sign. It means your child has the physical ability, but it may not mean that the skill is readily applied with meaning. Your child may be able to memorize every person and statistic on a video game board, but not use money appropriately. The purpose of assessment is not to downplay your child’s skills. In fact, I often end up recognizing far more prerequisite skills than parents were aware the child has. The purpose is to identify the first step to target in a skill, to combine a well-known skill with one that is difficult so you can maintain motivation and engage your child where they are.

Parents Have a Better Feel for Their Child’s Social, Emotional Age

Recognize that children, no matter the nature of their disability, are more similar than different to their typically developing peers. Sometimes the behavior or responses are more typical to a younger child, but they are still moving along that ubiquitous bell curve, just at a slower pace. One example of this is with a young girl I have worked with for 7 years. She is considered to have a severe form of autism. My sweet friend is functionally nonverbal. Her school did not believe us when we said she could talk. Until last year they did not attempt to make her talk. She can talk at home. It is stilted, and often just a few words, but her other response is aggression. When we moved from talking and reading single words to reading and using sentences she became very angry! Her mom would say, “I don’t know what happened.” I smiled and said, “The only difference between your daughter and my daughter is my daughter has the words to rant when she doesn’t like a subject we are studying. She also threw tantrums to avoid difficult things, but at a younger age.”

We must look at their development when we apply skills. Where are they socially emotionally? How would we help support any child at that social emotional age? Would we set limits? Give more visual cues? Give them a way to express themselves? The answer is yes, but the actual tool changes depending on their age, and an actual assessment of this age is much more likely for someone who lives with the child. For my friend, I use an abacus. Every time she responded, she moved a bead over. When all of the beads were moved, she was done with her work. If it was particularly difficult, I let her move two beads. When all her beads are moved, she is done. We need to teach coping skills when kids are frustrated, and recognize if it was truly easy they would be learning it. Some valuable coping skills include having pictures that represent emotions. When we are really upset and frustrated one of the first skills we lose is our ability to communicate. This is a human response. We learn to cope, in good or bad ways, and most often in the way that is modeled to us. For children who have limited verbal skills this could be modeling a physical activity. The next time you are frustrated, or open to pretending you are frustrated, throw rolled up socks at a target. Have a place where you can safely stamp your feet. Sometimes deep breaths are not enough, especially for children who struggle with poor impulse control. But if we develop a habit of a safe physical outlet when words fail, that is what these children will use. Then you have to acknowledge how proud and happy you are that they were able to handle frustration in a productive (versus destructive) way. By the way, yelling is ok with me, but I recommend using the bathroom. Giving a child permission to be angry is not the same as permission to be destructive or disrespectful.

Responsiveness and Flexibility are Important for Special Needs Children

The beauty of an eclectic education is that your resources and tools can change and evolve with your child. Traditional schools are not capable of this type of responsiveness and flexibility. While discrete trial training is currently only recognized as a tool used with children who have autism, it is actually used in many settings with a very eclectic, infinite range of items. First, identify the steps needed to teach the skill. That may sound simple, but in reality it can be far more complex. We do not realize how many steps there are to skills we hardly think about. Consider getting a drink of water. You must know how to find the cup, how to find the water, ask for help if it is needed, open a lid, or turn on a faucet, hold a cup, recognize your mouth, be able to swallow, be able to place the cup down…. So the first step often is going to depend on your child. Some children learn better by hand over hand prompts, some learn better by watching a video of the process, some learn better by a flip card book of the process. If I were teaching it to one of my students, I would guide them through the entire process, and slowly decrease support as skills are gained. Here is the discrete trial training part. You would only use enough water for one sip or gulp, and then you would repeat the process 4-5 times. This is helping the child build a habit. It becomes easier with each practice just like any other habit. This method can be applied to anything, but remember support is provided throughout so it does not become frustrating until the support is not needed.

Errorless Learning Is an Important Strategy

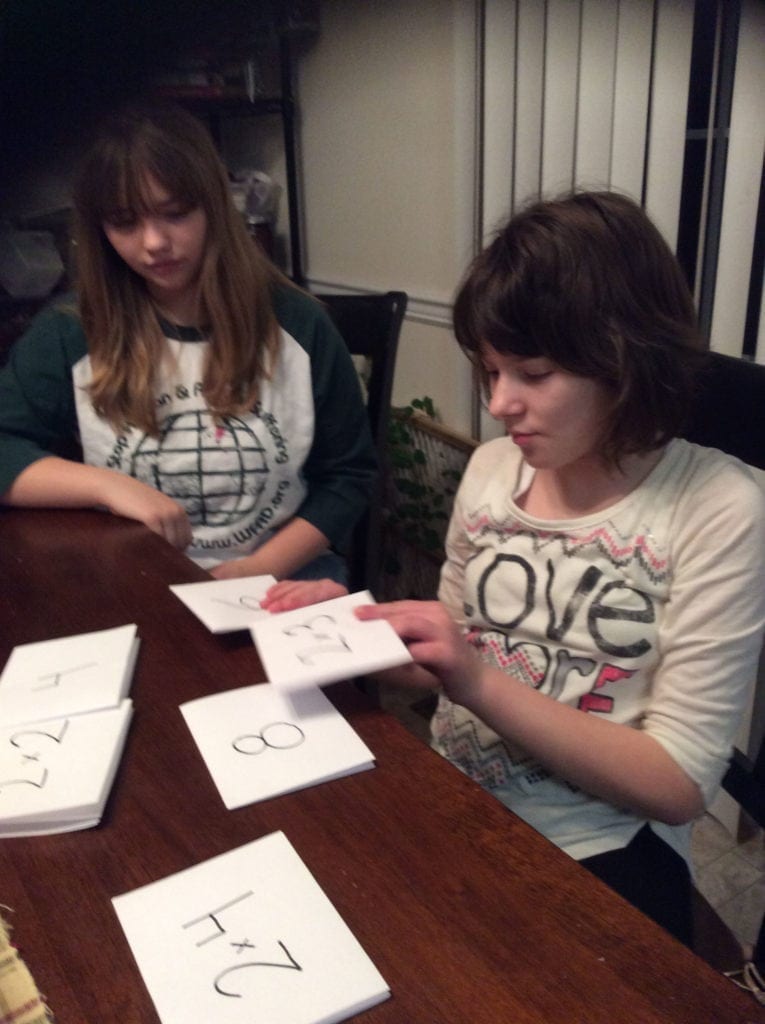

Errorless learning procedures can simplify your day, provide the appropriate support, and change as your child needs. An example I use for teaching reading and writing involves using picture cards, word cards, and tracing. This is basic. You do not want to be too creative, or it becomes distracting. When teaching the word “bear” for example, which does not follow phonetic rules, use a picture with the word bear on it. You will ask the child to read the word, “bear”, and then put a few more pictures with the words under them. You will have your child point to the word bear, and read it. Next you will have cards with the words on them, no more than three or four, and ask him or her to match the words. Then you will ask for the card that says bear, without the picture. You may end the session with the book “Brown Bear, Brown Bear …” and have the child read every time the word bear appears. The next word you work on, may be brown, or see. The book you are reading can help to determine the words you teach because of the rhythm and cadence. Just like learning a song, this makes it easier to remember the words in the book. Alternatively you might start with a special interest of the child’s, or with something you think will engage them. This does not happen overnight! It is more important that it is fun and engaging to support motivation and curiosity.

Movement Helps Kids Stay Focused

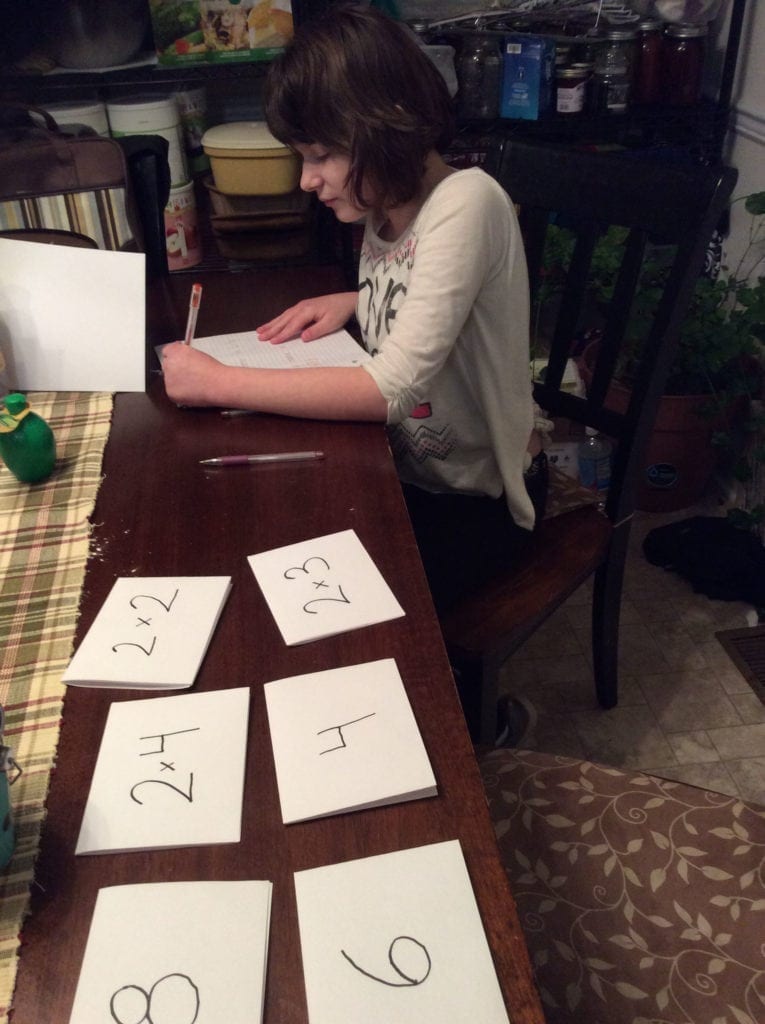

If your child struggles with low attention and poor impulse control consider having them sit on an exercise ball. Maintaining balance and doing work keeps their brain and body busy, so does chewing gum. Now for the eclectic, academic piece: Divide a table into four spaces, or you can use each room of the house to represent a different station. The individual components will depend on your child. Start with his or her baseline skill and increase it as he or she develops new skills. The first station might be math. At this station one, two, or more problems, depending on your child’s ability, will completed. When those are done, your child moves to the next space/seat and reads a page and answers questions verbally about the page. If there is a written answer, he or she moves to the next station and provides a written response. Consider incorporating some errorless strategies into this, draw a line to a correct response, or trace the correct response. After that, move to the fourth space for a physical activity, one that increases attention building like a puzzle or taking one turn of a game. Good game choices are something like History timeline where you place a card or two in the right space. Then you will return to the beginning and start all over again, until you have gotten through the project or subjects or activity you are working on. Try to have more difficult activities followed by an easier or more preferred one.

Reinforcements can Help Motivate

I often hear from people that they will not “bribe” their children to do something they should do. A bribe is giving someone something when they want them to do something that is wrong, illegal, or unethical. A reinforcement is a reward for a difficult job that is well done. It gives kids a reason to do the job instead of avoiding it. Just remember, if your child does not seem motivated by the reinforcement, it is not reinforcing the skill! The range of things that can be used as reinforcements are infinite, choose a different one.

Learning Is Infinite

Be realistic about goals for your child, but do not let anyone limit your child either. If the goal is that your child can sign their name, do not fill his or her day with handwriting practice. Instead give them opportunities to trace their signature several times a day every day. Make it meaningful for them. They want a new video game; write a receipt they have to sign their name to. Have them send postcards to family members, and trace their signature. Have them put labels on favorite belongings, and sign their name to it. Then identify the next skill that is important and meaningful to them. Working in this incremental way can help your child to make great strides, as little by little soon becomes a lot. The last main point I wish to express is this: learning itself and the strategies used to help people learn are infinite.

Christina Keller has a bachelors degree in Child-Life Psychology, Masters in Clinical Behavioral Psychology. She has worked supporting families and children in education and early intervention for a combined 20+ years, and homeschooled her own children for Past 5 years. Christina learned the most working with amazing families who have children that teach her new things every single day, and by being involved with the constantly evolving lives of her own children.

Check out our previous post on homeschooling high school here.