Mar 10, 2017 | Kate Laird

Why Study History?

History is our story, the record of our triumphs and tragedies. Without history, everything is new and surprising; history does not predict the future, but it narrows the possibilities.

The best way to learn history is to immerse yourself in the study of it – through historical television dramas, movies, historical novels, and by reading history, particularly one that takes both a social and political approach. Children love learning what other children’s lives were like, but even older students (and adults) like their history to read like a novel.

In teaching history, remember the twenty-year rule: do you want your students to know this fact in twenty years? I can remember a phrase on a history test: Harley-Smoot, probably because Smoot is such a fine name (or maybe I just remember it from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off). I can’t match it with any detail, however. It turns out to be Hawley-Smoot Tariff. Does it matter? I can always look up the name (as I did writing this paragraph). I do want my daughters to remember that a protectionist tariff contributed to the Depression, but I’ll save that for high school. In elementary school, the Depression is Dorothea Lange’s haunting photograph of the “Migrant Mother.” In middle school, it is Cinderella Man and The Grapes of Wrath.

The most important thing in elementary and middle school history is to encourage students to care about history, to see history as something that happened to real people whom they find interesting. That caring and that interest will fuel the hard work it takes to learn history at a more complex level, but chances are, your children won’t find it hard work, because interest will turn the page for them.

Teach History as a Story

History is interesting. Remember that. Countless teenagers drop out of history classes as soon as they can, moaning history is boring! If your students think history is boring, you’re not teaching it right. In many countries, world history is often condensed to a single year of secondary school – no wonder far too many students hate it: endless memorizing of dates and key terms, thousand-page textbooks, dry, dreary accounts of dead men.

I became a student of history because:

I heard stories from one grandfather about World War II in the Pacific; I read the scrawled handwriting of my other grandfather of his days in the Irish Rebellion. My grandmother told me stories about her parents, gold and silver mining in Nevada. She showed me pictures of her mother in a long, flowing white dress amongst the dirt and dust of a mining camp.

I found gravestones in a field.

We drove past a house with a Trojan Horse in the lawn, and my father filled the next hour with a recap of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

My mother invariably made me go to bed in the middle of the Disney feel-good movies on Sunday night, but she would let me stay up and watch any of the British historical dramas on PBS: The Flame Trees of Thika, A Town Like Alice, Danger UXB.

My father read me stories of King Arthur, Fionn mac Cumhaill, and Cuchulain.

I read books – Little House on the Prairie, Carry on Mr. Bowditch, Tale of Two Cities.

I accepted bribes – “We’ll take you to see Excalibur if you first read The Once and Future King and a Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court.”

Children’s stories, television, books, and ivy-covered ruins: that is how I came to love history. Old photographs, journals, and a gold buckle I could mark with my fingernail made me a historian.

In addition to being a pleasure, learning about history through stories is also the best way to remember it. In Why Don’t Students Like School? Daniel Willingham has an entire chapter entitled, “Why Do Students Remember Everything That’s on Television and Forget Everything I Say?” The answer appears some pages later:

The human mind seems exquisitely tuned to understand and remember stories – so much so that psychologists sometimes refer to stories as “psychologically privileged,” meaning they are treated differently in memory than other types of material. . . . [S]tories are easy to comprehend . . . stories are interesting . . . stories are easy to remember. (51-53).

History is simply a collection of stories. In more advanced work, history is analysis and interpretation of these stories, but the story is always the basis: what happened?

It is far easier to learn material presented as a story than it is to learn the same material in the condensed, often dry language of the history encyclopedia or textbook, even if you have to read a hundred pages to learn what takes ten pages in a textbook. The hundred interesting pages will feel like nothing to those with reading stamina; those ten pages can be a slog for even the best readers.

Teach History Chronologically

Most American schoolchildren study history as if someone had taken a deck of “important historical moments” cards and shuffled them. Here’s the Core Knowledge Standards for history:

First graders study early world history, modern Mexico, and early American history through the Revolution and westward expansion. Second graders jump back to Early Asia, followed by Modern Japan, followed by Ancient Greeks, then the US Constitution, the War of 1812, and onward to the Civil War in American history. Third graders study Ancient Rome, the Vikings, and in American history dive backwards to the Colonies.

I much prefer Susan Wise Bauer and Jessie Wise’s internationally-focused schedule described in The Well-Trained Mind, where students study world history in three cycles of four years, although I do have some disagreements with Wise and Bauer on their techniques and methods of studying history. History happened in chronological order on our three-dimensional planet. Geography, climate, and the behavior of the country next door (or often on the other side of the world) has profound influence over the way history unfolds, and thus for the clearest understanding world history and geography must be studied as one overarching course, rather than splintered into either nations or themes.

Sample History Sequence:

Developing Civilizations (to 500 CE)

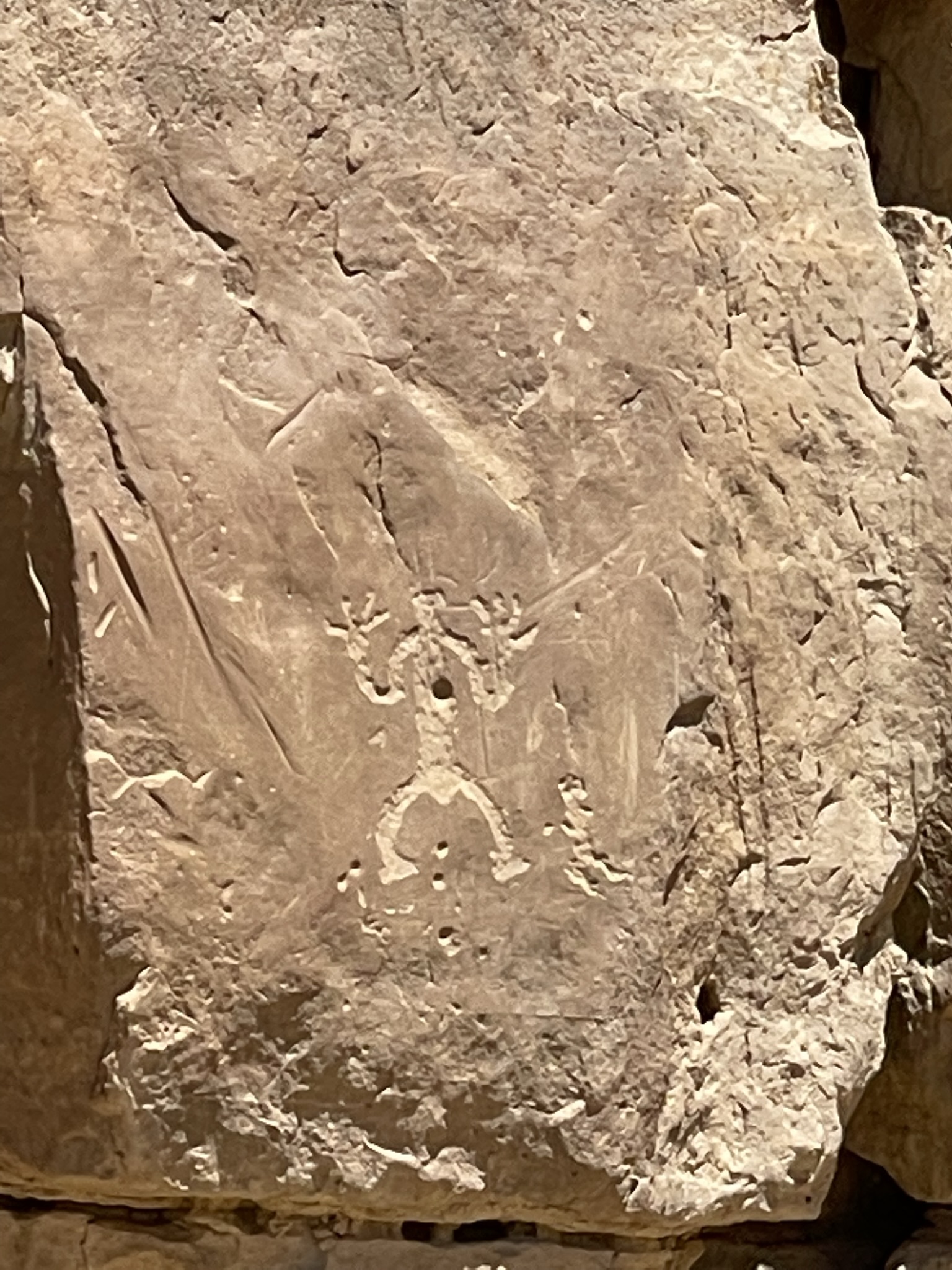

- Becoming Human

- Human Migrations / Hunter Gatherers

- Early Farming

- Ancient Civilizations Mesopotamia & Egypt

- Ancient Civilizations China & India

- Mediterranean 2000 – 800 BCE

- Mediterranean 800 BCE – 500 CE

- Beginnings and spread of global religions (Hinduism, Confucianism, Buddhism, Judaism, and Christianity)

- Han China

- Your ancestors

Mobile vs. Sedentary Nations (500-1600 CE)

- Ancient Civilizations Americas

- Ancient Civilizations Sub Saharan Africa

- Nomadic Tribes invade Europe

- Origins and Spread of Islam

- Christian Empires / Crusades / Protestantism

- Tang / Song China

- Nomadic Tribes invade Asia / Yuan / Ming China

- European countries invade Americas (“Columbian Exchange”)

- Renaissance Europe

- Your ancestors

Europe vs. the World (1600-1850)

- Sea Trade & Warfare: beginnings of a global world

- Qing China

- Mughal India

- European colonialism

- Africa enslaved

- US Revolution / Constitution

- French Revolution / Napoleonic Wars

- Industrial Revolution Europe

- Japanese Isolationism

- Your national history

The Global World (1850-2000)

- US Slavery / Civil War

- Social Effects of Industry

- WW I

- Economics: Capitalism and Communism (Great Depression / Ukraine Famines)

- WW II

- Cold War

- Middle East

- Latin America

- Cultural Changes: liberalism & fundamentalism

- Your national history

Download this list as a PDF

It was a struggle to limit this list to ten points each year. It is not a fixed list, of course; it is certainly biased, but I have highlighted cultures and ideas that still have influence in today’s world. My own failing in history is usually to try to cover too much in a given year: I want my children to know everything! Your local library (and Interlibrary Loan), a book of timelines, and a historical atlas can help you put together a history of the world at a listening or reading level suitable for your children.

Historical Sources

In history, we talk of three kinds of sources: primary, secondary, and, for lack of a better term, tertiary. Primary sources are what working historians rely on: the original documents, whether they are official (charters, agreements, constitutions), domestic (diaries, tax records, oral histories), or published books from the era (Homer, Plato, Shakespeare, Thomas Jefferson). Students should do research and analysis of primary sources and read some of the great books of our past in middle school and high school.

Historians use the primary sources to produce secondary sources. These range from articles, to books for an adult audience, to monographs for other historians. These secondary sources are the best way to teach history, because they provide a wealth of details, personal stories, and interesting information that makes history memorable and important. The difficulty with these books is they usually require strong reading stamina. Many students won’t be ready to read them until high school, which leaves middle school as the most difficult age to source good history materials. There is a new trend of journalists writing secondary source histories, often based on historical monographs and their own primary research, creating very readable, exciting books about the past, which bring history alive for middle school and older students.

Tertiary sources are the third level, the least lively, the least readable, and often the least accurate. Here are your textbooks, which often are simply based on other people’s (or other committee’s) textbooks; here are your encyclopedia entries, your Wikipedia, and the summary histories of a region (or sometimes the entire world). These tertiary books have an important place in the study of history, but as a spine, or a general reference book, rather than the sole source of information.

Historians know that every writer of history has an agenda; they are acutely tuned to perceiving bias. Students are seldom taught to take the same approach. It’s obvious to most readers that primary source material will have biases, but it’s important to remember that secondary and tertiary materials are also the product of the author’s worldview, which is often simply better disguised than it might be in primary sources. Unfortunately, most sources of historical reading available to students fall into one of two poles: absolutism or relativism, with no guidance as to how to understand or even detect those biases. Most history books for children, particularly in the early grades, fall into the absolutist category: jingoistic platitudes about how marvelous one’s own country happens to be. Adults who were brought up with absolutist history bristle with anger at relativistic history which asserts that all cultures and mores are equally valid. Real history takes a middle ground; it reports the good and the bad, and it evaluates and argues.

For his article, “On the Reading of Historical Texts,” director of the Stanford History Education Group Samuel Wineburg analyzed the thinking process of professional historians versus that of strong American high school students, and discovered that this awareness of bias was one of the key differences in the way the two groups perceived historical writings. The students had not yet learned to mistrust their textbooks. Without realizing it, I taught my children this key skill early on, because many of their books were so biased that I couldn’t let the notions stand.

Throughout our history program, I have emphasized broad conceptual knowledge over rote memorization of dates and people. I’m not convinced that remembering the minutiae of history is as important as having the global picture of the past ten thousand years. I do think that reading that minutiae is important, however. Too many history books take a “dates are boring” approach and it can be very difficult to figure out what date the author is talking about. Dates are important. They cost nothing to read, as they are a very fast shorthand to fixing events in your mind. Authors too often think that students will simply glaze over if they use a date, but I don’t think that’s true. Readers do not necessarily retain the dates, but knowing the date helps them make better sense of the paragraph, which may help them better remember the ideas in the paragraph. Remembering exact dates, however, has a high cost for most people: flash cards and drill.

Learning History

Sample Stages of History Learning

Grades K-2: Teacher reads a history story aloud; students draw a picture and gradually transition to drawing a picture, writing a caption, and finally writing a short summary of the story and sketching a blackline map.

Grades 2-4: Teacher reads a history story aloud; students write a half a page summary and sketch a blackline map.

Grades 4-6: Teacher or student reads a history selection aloud; students either write a half page summary or take notes and make rough outlines of the material, make map sketches. Every six or eight weeks, students write 1-3 pages either describing what happened in a historical event, or discussing why and how something happened, or compare and contrast two events.

Grades 6-8: Students read assigned readings from textbook and adult-level history books. Textbook readings should be accompanied by notes or outlines, followed by a four or five line summary of the most important ideas. When working with longer books, students can take notes and annotations, and should write a short summary at the end of the book with a bibliographic entry. Map sketches continue to be valuable learning tools in geography and understanding how and why events happened as they did. Every six or eight weeks, students should write a 3-5 page paper (topics can be assigned or free choice), with or without outside research. Most papers should contain description, discussion of the events and perhaps a comparison with another event in history. In addition to discussing the reading, papers could also discuss the relationship of historical novels or films to the actual events of history.

Grades 9-12: Students read historians’ monographs, narrative histories, selections from a world history textbook, watch movies, read novels (both modern historical novels and contemporary literature from the time period), and listen to lectures from MOOCs or commercial programs such as the Great Courses. Emphasize note-taking on lectures and readings, and date memorization if they plan to take standardized exams or APs. Students should write one or two 5-8 page papers every semester and practice with essay exams, with both general questions and document-based questions. Course-work will need to be structured around State or National requirements for high school, and the schedule may be determined by any pre-college testing your student chooses to do.

Projects: What about all the history projects – building models, baking bread? Are they necessary? I don’t think so. If you and your children enjoy them, great, but if you don’t, feel comforted that reading, writing, and drawing are the most efficient ways to learn history (and build reading and writing skills). I always found it more efficient to work on reading and writing in “school” and leave plenty of time for my children to build mud castles on their own.

Choosing Historical Readings

For homeschool teachers who may have been heard to shout “history is boring!” themselves, teaching your children is a wonderful way to learn all of those stories that you missed out on in your own schooling. Read the stories along with your children, watch the movies, find out about your family’s story, or one like it if your own is lost. Read historical novels.

On your own time, try some narrative history books (that is, books where history is presented as a story). Try Cod, Nathaniel’s Nutmeg, Longitude, Mayflower, 1776, and so on. After the success of 1776, various authors have come out with books centered on a single year: 1491, 1492, 1493, 1927, 1968. These books capture a moment in time and bring it alive to modern readers, adults and strong middle school readers alike.

When you’re choosing books for your children, ask yourself, is it interesting? Younger children will remember the Usborne Time Traveler series; when they’re a bit older, they can learn about Rome from Caroline Lawrence’s Roman Mysteries.

Going further back in pre-history requires even more work of the teaching parent, because scientists’ understanding of our pre-history is developing faster than the pace of children’s books. Every one of my children’s early books (and their high school textbook published in 2004) maintained firmly that there was no interbreeding between humans and neanderthals; recent science shows that as much as twenty percent of the neanderthal genome is distributed through human populations today. But instead of fretting about these changes, I welcome them: it demonstrates that history is an ongoing discovery, just as much as biology or astronomy.

Secular Programs

Religion is obviously an important component of history. Students must have a familiarity with the major religions of history and understand how religion both affects and is affected by historical trends. However, many homeschooling programs privilege one religion over the others. For example, the popular Story of the World series by Susan Wise Bauer have a notable Judeo-Christian bias. Biblical stories are presented as fact, while other religions’ stories are presented as fable. It does not meet the requirements of a truly secular program.

Like many other secular homeschooling families, we found it possible to use Story of the World successfully. If you choose to use this series, I would recommend using the books only (not the add-on workbooks), and reading the material aloud to your students for volumes one and two, even if they are capable of doing the reading themselves. This will allow you to skip around, modify the order, or simply point out bias as you see it. Learning about bias is an important history lesson in itself.

Pandia Press offers History Odyssey, which uses Story of the World series as a spine in elementary school, but re-orders the chapters and skips the most biased ones – the editing work is done for you. The syllabus includes a lot of outside reading, but with advanced planning you should be able to order most of the books through Interlibrary Loan if they’re out of your budget range.

My dream curriculum would follow my topic list above with four children’s books on each subject in elementary school; a full-length adult popular history and a novel, biography or movie on each topic in middle school; and a comprehensive study of primary sources, historical monographs, and a textbook overview in high school.

Many programs use the Kingfisher History Encyclopedia as their spine in middle school. This is a good reference book, but it shouldn’t be used as the base reading for a program. Strong readers will be better off with a good high school textbook, such as Duiker & Spielvogel’s Essential World History or Felipe Fernandez-Armesto’s The World.

I started off with Duiker and Spielvogel when my daughters were in fifth and sixth grade, because I was desperate to keep up with the four year cycle. It was too difficult. I read it aloud, and that taught them a bit about reading about history, but in retrospect, I might have done better to deviate from my plan and teach US history with Joy Hakim’s History of US, while letting their reading levels strengthen through free-choice reading. (I recommend The History of US with a few caveats: it can be slightly jingoistic and the format is extremely busy. My children preferred to flick through it and “read the distractions first,” looking at the pictures and the sidebars, and then returning to read the main text of the chapter.)

Three cycles of world history over four years is my ideal, but don’t be afraid to rearrange it to suit your family, reading levels, or available resources. One of the great virtues of homeschooling is that you can make school match the needs of your family and your children. If your program turns out students with a broad overview of historical events and an interest in history and historical literature, you have succeeded – even if they don’t know about the Hawley-Smoot tariff.

History Summary

- Teach elementary and middle school history chronologically

- Use writing to expand understanding

- Textbooks help with the big picture, but trade books are more memorable

- Use literature and film to complement historical readings

Check out our post about how to put together the best science field trip here.