As the parent of a special needs kid, the last thing I ever expected to feel when we began our homeschooling journey was relief. But that’s what we got. As the single mother of a child with nine different diagnoses, I don’t use the word “relief” lightly. Homeschooling my daughter astounds me.

It certainly didn’t start that way. I grew up believing that homeschooling is for weirdos and the proper thing to do is for kids to go to school. As the child of two public school teachers, my education was constant. If our school days off didn’t match up, I spent the day at their schools anyway.

To say I felt like a failure when first considering homeschooling my own child is a massive understatement. I stewed in my ignorance over what homeschooling looks like for years. I never chose it. I was forced to it when the public school system failed us so intensely. Now, certainly there are public educators who do extraordinary work with special needs kids, and certainly there are schools where kids may thrive. This was not the case for us in any of the five schools my girl had attended by the time she made it to the end of second grade.

Our experience with schools was arduous.

Before beginning elementary school, she loved to learn. There was a wonder and joy apparent across her whole body as she picked up new skills. When elementary school began, the only sensation she experienced each morning, before breakfast or even before getting dressed, was dread. I mourned the loss of that love of learning. I never in a million years expected to see that love of learning resurface when we began homeschooling, but it did!

The journey to and out of brick and mortar classrooms has sometimes been cruel, often exhausting, and occasionally extraordinary. That’s life with special needs kids.

To be the mother of a special needs child takes the mother bear instinct to vigilant war leader level. Remember not sleeping when your baby was an infant because you had to make sure it still breathed? That feeling can last forever when you are the parent of a special needs kid.

My child has severe anxiety. She screams and runs when she is triggered by such small things as someone sharing the story of a dog that is big and loud. It’s impossible to be out in the world and not have her triggered several times a day.

To be a single mother and be unable to hold a job because your child’s elementary school calls with the news your kindergartner was missing on an open campus for 20 minutes is untenable. That school is renowned for its academic program. It’s so elite they have an 800-deep student waitlist. She literally won the lottery to begin attending as a kindergartner. I had been over the moon to see her begin to learn a new language, to access full arts and physical education components in a state notorious for dropping them.

None of that mattered. The next day I sat outside in the parking lot crying and shaking, unable to drive away for two hours. It wouldn’t be the last time. And that was before she had epilepsy. Her first seizure would come the following year and would be an hour long.

But kids go to school, right?

We struggled mightily, trying to make the system work.

When the district fails to provide a safe and accessible school environment, we special needs parents have to fight the establishment for our children to have equal access to education. We would do anything for our kids. And while every family probably worries about not fitting in, the vulnerability around acceptance for both parent and child is largely increased when that child has special needs.

Hope dies as a system meant to occur in partnership with parents becomes adversarial. It’s devastating. And over the next four years, the battles and the fears only grew. There is a weary and glazed look that often comes over the faces of many special needs parents when they hear the letters IEP.

“IEP” stands for Individualized Education Plan. An IEP can provide measures of protection and opportunity for students and staff by articulating specific goals and methods appropriate to meet the acknowledged needs of the child. Most of that never got accomplished for my kid. My daughter’s anxiety is so severe that when it flares, she feels panic akin to being trapped in a burning room. She deserves the cooling and calming of experienced care providers who know how to de-escalate and help her.

My child’s public school had not the time, the training, nor the impetus to do any of those things. Instead, when the principal called me in, I sat with my mouth agape as she said that my first grader was suspended for having a panic attack in the principal’s office because they wouldn’t let her call me. In her panic, she hit the principal. Had they let my daughter call me, none of that would’ve happened. There’s no way we were going to make it through 13 years of this.

But kids go to school…don’t they?

I took the fight to the next level.

I called special needs parent organizations to help me learn how to fight effectively to get my kid’s needs met. I ended up speaking to disability rights lawyers. I learned the language and documented everything. I fought for her to have the “least restrictive environment,” to have “free appropriate public education.”

My girl performed in the school talent show three days after she had fully recovered from her second seizure, when she’d been given the doctor’s go-ahead to return to school. But the school wouldn’t allow her back in the classroom for a month because the teacher was uncomfortable with epilepsy and was unwilling to be educated about it. I opened a case with the Office of Civil Rights. But no help came.

Behind my back, the PTO and staff referred to me as “Seizure Mom.” And though I would get my daughter up for school an hour and a half before it began, though we had a visual schedule, and though she had everything laid out to have a successful day, five minutes before we got in the car she would have a tantrum. That meant we were 20 minutes late. The principal would then condescendingly invite me into his office to “chat” for several minutes about how irresponsible it is to be late to school. Properly achieved IEPs can include no penalties for tardiness, but they don’t remove the stigma.

And hey, to own that title of “Seizure Mom” for a minute: One in 10 people will have a seizure at some point in their lives. One in 10. One in 26 people will have epilepsy. It is a huge number, more than cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, and Parkinson’s disease combined. It’s as common as breast cancer in this country. I could go on. You’re going to want to know how to help out if someone has a seizure.

Maybe it was just that school.

We learned that the dysfunction was systemic.

It wasn’t just that school. At this point I questioned if it was possible to find a safe schooling environment at all. There were services that needed to be put in place for the benefit of everyone, including the other students in her classroom and the teachers. We needed the district to complete academic testing in order to receive services. But they wouldn’t even do the legally-mandated testing. At another school, filing an 88-page complaint to the state yielded nothing. Though the district was found to be grossly out of compliance, the only result was that the district should reprimand themselves and move on.

We moved halfway across the country to a state known for a higher quality of both education and medical care. But she still wasn’t safe in public school. She frequently locked herself in her locker and screamed. With 30 kids in her class and one teacher with no classroom aides, it was likely the class bully would mercilessly injure my child while she had a seizure. The IEP team said my kid didn’t need an aide, so I still couldn’t work because I kept having to go to my child’s school. Although I did discover that Domino’s delivers pizza to school parking lots, sitting in my car every day in February in -6° weather waiting for my kid to run out the door is no way to live. It’s all beyond tolerance.

I began to accept that no, all kids do not go to school.

No matter what society demands, we just couldn’t do this anymore.

Our society is so attached to the public school rhythms that we even deny mother nature’s own cycles. We say that school starts in the fall, even though technically autumn begins about a month later. We say summer starts right after school ends though solstice is weeks away.

Well, I say the experience we had with public school was definitely out of sync with what works for my daughter’s true nature.

Finding relief is a process.

Remember at the beginning of this odyssey I mentioned relief? That my daughter’s love of learning is back? There is no more panic and dread about school.

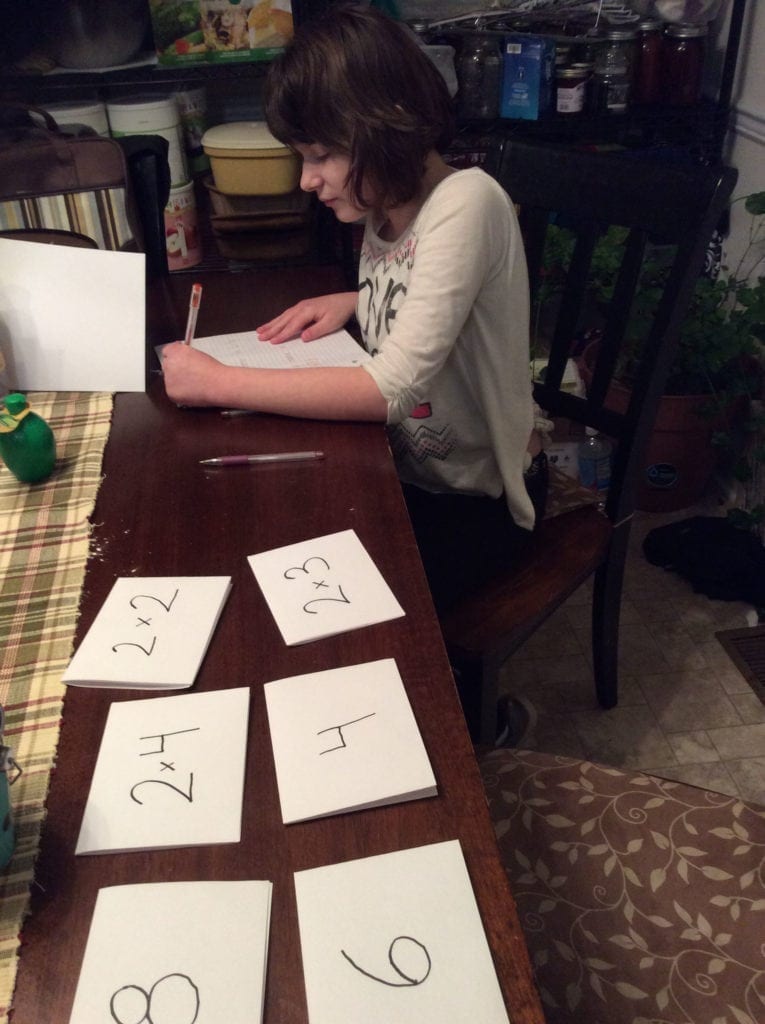

At public school she would crumple up a page of math problems, scream, throw it at the teacher, and run away crying.

It took seven months of emailing, calling, documenting, resourcing, bringing her to school, plus an impromptu visit to the district office of the head of special education with my daughter in tow, to get a school psychologist from another district to come do an evaluation.

This excellent psychologist, who was shared by five different schools, discovered there is a disconnect in my kid’s fine motor skills when her brain knows what it wants her hand to do. When the hand doesn’t comply, the disconnect triggers an anxiety attack.

It’s been a long journey.

Now that we have deschooled and are at home, her anxiety is significantly lessened because we took the time to discover what it was that she wants to learn about, to find out how she learns. If she gets stressed we can take a break, find a different route to solve the problem, do what makes her feel safe and soothed.

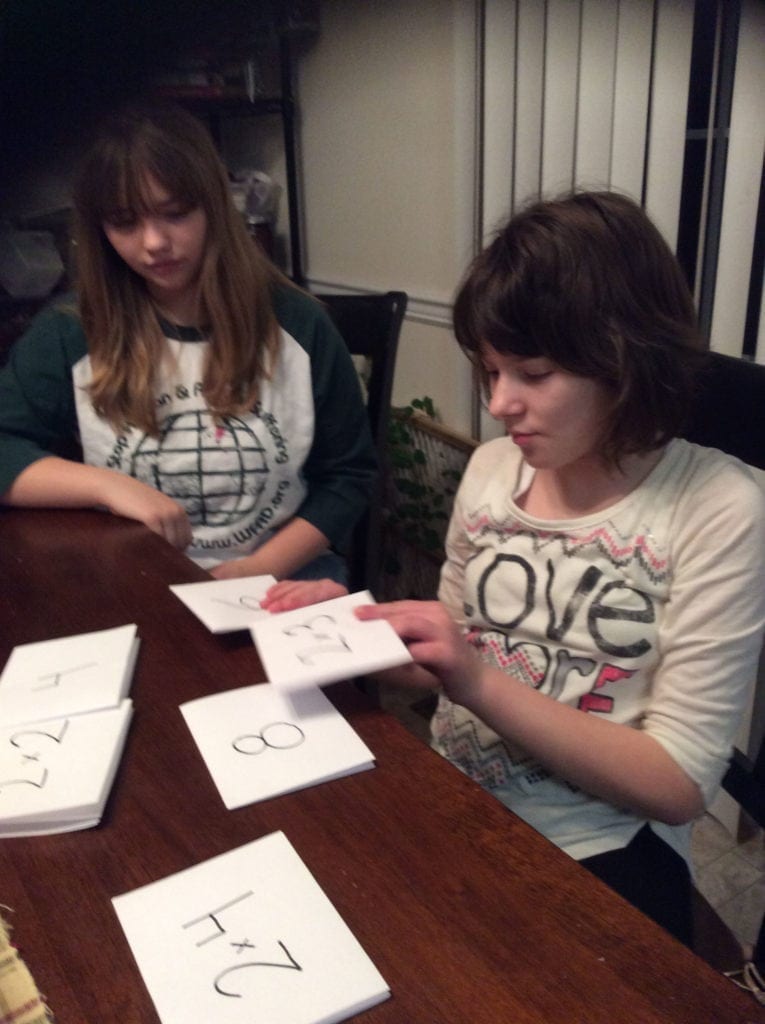

She is teaching me just as much if not more than I am teaching her. Now, she brings me a page of math questions unprompted. She asks sweetly if I can review it with her. She can achieve higher levels of math than school testing indicated. My girl sits at the computer and plays math games with unwavering attention and enjoyment. She has a sense of pride in her work. I have profoundly missed that in her.

I almost missed it completely because I thought homeschooling had to look like setting up a public school at home. And that is just nuts. Remember how I said I was raised by teachers? I had to deschool as well. Perhaps even more than she did. I had to give myself a chance to heal, to see that our children naturally lean into learning all the time when given an environment where they are comfortable and encouraged.

Homeschooling doesn’t have to look like anything other than what you determine is most productive for yourself and your kid.

Relief is everything.

To be on a team with my child that gives her the time and space to learn is such a relief. To raise a special needs child is a constant endeavor that requires enormous ingenuity, resources, endless effort. Relief is a treasure for special needs families. Relief is something we will never, ever take for granted.

There are so many perks that come with homeschooling… getting up later in the day, learning in pajamas on a Sunday or in the middle of July if we feel like it, to name just a few.

Sure, there are days when her diagnoses make it difficult for her to move forward, but that is what treatment teams and time to learn how to cope and move through things are for. When we go to doctor and therapy appointments, we never have to miss a day of school. Homeschooling gives us that time.

There is a grace and breath to homeschooling that is such a gift. I could write 10 separate articles about what it has taken to financially, emotionally, culturally get us to this point. But what matters is that my daughter is happy to be learning. I’m so proud of her. The relief that comes to us both, to experience that love of learning, means just about everything.